The information provided in this blog is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice. If you have questions about your health, speak to your GP or specialist.

September is Sickle Cell Awareness Month, and we are back with another annual blog to support raising awareness of sickle cell disorder. As you know, we have recently returned after a short break. One of the Cultured Health Partner’s family became unwell. They ended up making a trip to A&E after presenting with pain, eventually after 5 hours in A&E a doctor asks, “Do you have sickle cell?”. At this point they had no blood pressure, pulse or oxygen saturations done. Those checks did not take place until 8 hours after they presented to A&E and they were not given sufficient pain relieving medication. More on that story another time. They eventually got assistance, sickle cell disorder was ruled out and they made a full recovery.

However, it made us at Cultured Health Partners wonder, if our team member was experiencing a sickle cell crisis that required hospitalisation, what care are they supposed to receive? Approximately, 17,000 people in England live with sickle cell disorder (Source). It is estimated in England, there were just over 32,000 hospital admissions in England in 2023-24 for sickle cell disorder (Source). Over the years there have been cases where patients have not received care that meets their needs and in some cases died from inadequate care in hospitals.

What is a sickle cell disorder crisis?

A sickle cell crisis, sometimes called a vaso-occlusive crisis, happens when the red blood cells change shape, becoming hard and sticky. This can block blood flow and oxygen delivery in small blood vessels and cause episodes of severe pain, often in the chest, abdomen, arms, or legs resulting in tissue damage, and potential organ damage in areas such as the bones, joints, spleen, lungs, kidneys, and eyes.

Another life threatening sickle cell disorder crisis, more prevalent in children is acute splenic sequestration crisis (ASSC) which can result in circulatory collapse due to the loss of circulating blood volume when large amounts of red blood cells become trapped in the spleen. It is managed completely differently to painful crisis. Healthcare professionals should be aware of such complications in patients diagnosed with sickle cell disorder.

For the remainder of this blog we will focus on painful sickle cell disorder crisis. These painful crises can be triggered by factors like dehydration, infection, or cold weather. While some people may be able to manage mild pain at home with prescribed pain relief, a crisis can become an emergency. People living with sickle cell disorder, should go to hospital straight away if usual pain medicine is not helping, the pain feels much worse than normal, you develop a fever (which could mean infection), have chest pain or difficulty breathing, notice sudden weakness or slurred speech, or if you feel unusually drowsy.

You can call 999 in an emergency, or attend your nearest A&E. You can also contact your specialist sickle cell team for advice or inform the A&E department to make your specialist aware.

How are people living with sickle cell disease treated in A&E?

People living with sickle cell disorder receive worse care than people with similar congenital disorders such as cystic fibrosis. The NHS Race and Health Observatory wrote the Sickle Cell Digital Discovery Report: Designing Better Acute Painful Sickle Cell Care which collates the experiences of people England who have experienced painful crises.

The report found that during painful sickle cell crisis, individual care plans were not being followed or acknowledged, delays in pain relief and poor recognition of severity, stigma, bias and mistrust based on treatment from staff. In some cases delays and lack of recognition of sickle cell crisis can devastating consequences. For Evan Nathan Smith (2019), Shen’iyah Green (2019), Tyrone Airey (2021), Darnell Smith (2022) and Dave Onawelo (2023) and who all attended hospital and sadly passed away due to delayed and improper care.

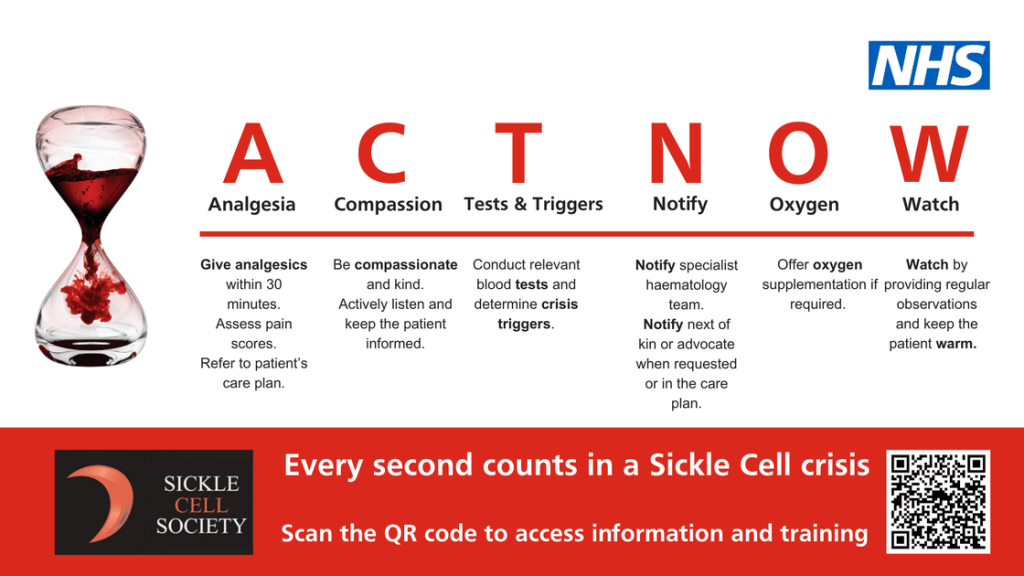

For Wayne Bailey (2022), he passed away in prison as the severity of his worsening condition was ignored, through the inquest it would later be confirmed he died of a heart attack as a complication of sickle cell crisis. In 2024, the ACT NOW campaign was launched in a few select hospitals (with the view to roll out across England) to prompt clinicians to act rapidly when a patients with painful sickle cell crisis—used in emergency departments (A&E), acute hospital wards, and ambulance services.

What should happen when I or someone I know goes to hospital with sickle cell crisis?

When someone with sickle cell disease arrives at a hospital in crisis, the response should be fast, compassionate, and consistent. National guidance state that patients experiencing severe pain must be assessed immediately and given effective pain relief within 15 minutes of arrival at A&E. This ensures delays do not result in prolonged suffering life threatening complications.

Staff should use the ACT NOW approach, developed with people living with sickle cell disease which reminds teams to assess promptly, control pain, and treat patients without hesitation. For many people from the Black Caribbean and Black African heritage who are disproportionately affected by sickle cell disorder, quick action can be the difference between safe recovery and preventable harm.

After initial pain relief, patients should receive a comprehensive medical assessment to check for complications such as infection, stroke, or acute chest syndrome (heart attack). Where needed, blood tests, oxygen monitoring, or even a red cell exchange transfusion should be considered urgently.

Care must not stop at symptom management: patients should be reviewed by staff trained in haemoglobin disorders and linked with a local specialist haemoglobinopathy team if not already under their care. NHS hospitals are increasingly supported by regional sickle cell, thalassemia and other blood disorder coordinating centres, which ensure that frontline staff have access to expert advice and that patients are treated consistently across the country.

Equally important is how patients are treated as people. Too often, people living with sickle cell have reported not being believed about their pain or facing stigma when asking for strong pain relief. What should happen is the opposite: every patient should be listened to, respected, and treated with dignity.

Clear communication, timely updates, and involving patients in decisions about their treatment are vital to rebuilding trust. NHS services are working to improve this, but ethnic minority communities must feel confident that in a crisis, they will receive safe, rapid, and equitable emergency care.

The information provided in this blog is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice. If you have questions about your health, speak to your GP or specialist.

For more information about what you can do during Sickle Cell Awareness Month, read our blog, support and visit:

Leave a comment